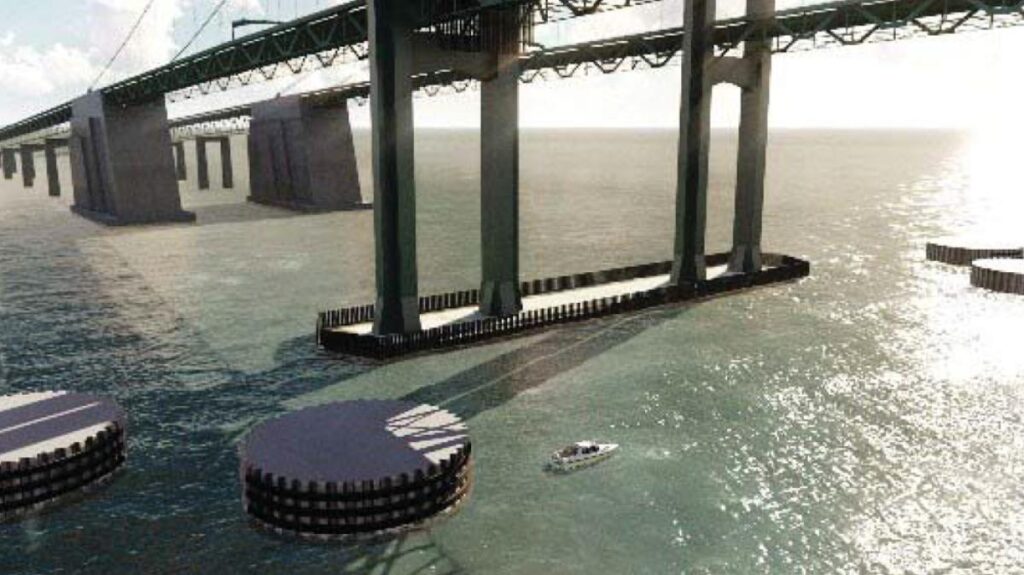

Photo courtesy of Richard E. Pierson Construction Co.

New pier protection cells will protect the Delaware Memorial Bridge from a vessel collision in the range of 120,000 deadweight tonnage (DWT), travelling at a speed of approximately seven knots.

Could it happen here?

That is the question Delawareans have been asking since watching the horrific images of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge collapsing after a cargo ship rammed it last month.

There are no guarantees, but efforts have been under way for 10 years to protect the Delaware Memorial Bridge from vessels even larger than the Dali, which hit the Key Bridge March 26, and the state has been running bridge loss scenarios for years, Delaware Live reported April 5.

Drivers on and near the Delaware Memorial Bridge connecting Delaware and New Jersey can take some comfort from the huge cranes that are part of a $95 million project to update the system that protects against ships crashing into one of the spans.

The structure carries traffic from Interstate 295/U.S. Highway 40 across the Delaware River.

R.E. Pierson Construction Co. of Pilesgrove Township, N.J., was awarded the construction contract to build the new bridge’s Ship Collision Protection System in January 2023.

Work began on the span late last July and is on target to be completed by September 2025.

The Delaware River and Bay Authority (DRBA) is installing eight stone- and sand-filled “dolphin” cylinders, each of which measures 80 ft. in diameter. Two will be on each side of the bridge’s piers to act as protective barriers.

“This is a $95 million insurance policy,” said DRBA Public Information Officer James Salmon. “You never think you’ll have to use it. You hope it goes untouched, but you will be glad you have it if you need it.”

Four dolphin cells will be installed at the piers supporting both eastern and western towers of the bridge and be located a minimum of 443 ft. from the edge of the Delaware River’s 800-ft.- wide channel, according to DRBA, a bi-state governmental agency that owns and operates the bridge, five airports and two ferry systems that connect New Jersey and Delaware.

Dolphins Designed to Stop Neo-Panamax Vessels

The Delaware Memorial Bridge project has been in the state’s River and Bay Authority’s Capital Improvement Program for 10 years, so planners are much further along than other states responding to what happened in Baltimore.

Still, Salmon said, “It’s not necessary to accelerate our timeline,” noting that two of the eight piles have already been completed. “We have an ambitious construction schedule and we’re moving as fast and efficiently as we can.”

The protection system is designed for a Neo-Panamax vessel, which is slightly larger than the container ship that hit the Key Bridge.

The dolphins are made of 540 tons of steel, 15,000 cu. yds. of sand, 140 cu. yds. of large stones and 4,000 cu. yds. of massive boulders at the top, with about 15 ft. of their structure visible above the water line.

They are designed to absorb the impact of the ship, preventing it from hitting one of the support towers, or steering it away.

“Our cells are designed to be sacrificial, but will stop a ship from hitting the bridge,” Salmon added.

The bridge spans were built in the 1950s and 1960s, and while they have been updated throughout the years to accommodate increasing vehicle traffic, the existing protection system had not been updated, even though the ships passing under the bridge today are much larger and faster than those of 60 years ago, Salmon said.

Ships crashing into the Delaware Memorial Bridge, which connects Pennsville, N.J., and New Castle, Del., are uncommon but not unprecedented. For instance, in July 1969, the tanker Regent Liverpool struck the bridge, requiring extensive repairs that would have cost around $7 million in today’s dollars.

Delaware Routinely Practices Its Response to Disasters

Meanwhile, the Delaware Emergency Management Agency (DEMA) conducts annual “Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessments” using different scenarios that test how disasters would impact the region and the state’s options for responding.

At least one in 2022 focused on how the state would handle a collapse of a bridge like the Delaware Memorial Bridge or the large bridges spanning the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal, noted DEMA Director A.J. Schall, who also serves as Gov. John Carney’s Homeland Security advisor.

In January 2017, DRBA had the Center for Homeland Defense and Security conduct a tabletop exercise involving a ship hitting the Delaware Memorial Bridge.

The next year, the bridge had to shut down for more than six hours after a leak of ethylene oxide from the neighboring Croda plant on the Sunday evening after Thanksgiving, an ultra-busy traffic day.

The C&D Canal is a 14-mi. sea-level ship canal connecting the Chesapeake Bay with the Delaware River. It includes six major automobile and railroad crossings, including the Summit Bridge, the St. Georges Bridge, and the William V. Roth Jr. Bridge.

Those spans on the C&D Canal are maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which did not respond to requests from Delaware Live for an interview.

About 20 percent of the project is being funded by a U.S. Department of Transportation BUILD grant, with the rest coming from bridge tolls generated by the more than 100,000 cars crossing the bridge each day.

Lessons Were Learned From Baltimore Collapse

The scenarios created by DEMA for mass-casualty events have included those involving bridge ramming and tropical storms closing the Roth Bridge.

“The people in Baltimore brought their A games to what happened there and that’s what we want to do here,” Schall explained. “You’re preparing for the unthinkable.”

He sat in on many of the meetings in Baltimore as officials there have dealt with the Key Bridge collapse and will learn more once it releases its after-action report in a few weeks. Schall noted that while there, he learned a few things to apply to Delaware’s preparation for the unthinkable.

“We’re going to reprioritize [how we handle our] Business Emergency Operations Center, which integrates local companies into the planning and improved communications in such areas as mass transportation, office schedules, outreach to other state agencies, and whether there’s a criminal presence in a given event,” Schall told Delaware Live.

It’s “one area I want to make work even if we do not ‘need’ it as much as other states like Pennsylvania and Florida,” he continued. “But I do feel vindicated a bit because we’ve done the bridge ramming scenario and learned where you become stressed. All bridges are critical to our daily lives and are treated as so.”

Read the full article here