Photo courtesy of Vermont.gov

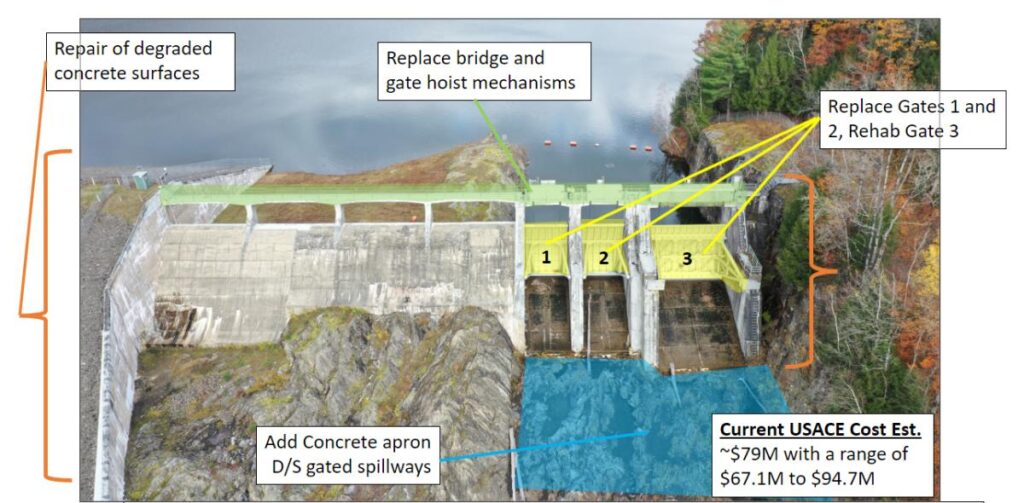

Recommended rehabilitation measures for the Waterbury Dam, per the USACE.

A year ago, as historic levels of rain fell and rivers jumped their banks in New England, Vermont’s dams felt the full force of the flooding.

At least five small dams failed entirely. Around 50 dams, at least, sustained damage requiring repairs by the state’s Agency of Natural Resources. And at the state’s key flood control dams — Waterbury, East Barre, and Wrightsville — water levels reached record or near-record highs, alarming residents who lived downstream.

For Vermonters residing along waterways or beneath dams, July 2023’s historic flooding drew attention to the state’s network of hundreds of dams, many of which are old, decaying or forgotten.

The disaster helped spark a sweeping reappraisal of how the state manages its waterways and the structures built on them.

Now, new legislation as well as an influx of state funding and a suite of new rules are slated to dramatically reshape how Vermont oversees its dams.

“It’s a big deal,” Neil Kamman, the director of the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation’s (DEC) Water Investment Division, told VTDigger. “The dam safety program is evolving significantly, [and] in a good direction.”

Month Filled With Close Calls

VTDigger noted on July 1 that last year at this time, as torrential rainfall soaked Vermont, water rose precipitously behind the Waterbury, Wrightsville and East Barre dams, the state’s trio of Winooski River flood control barriers.

On July 11, 2023, Montpelier City Manager Bill Fraser took to Facebook to warn, “If water [at Wrightsville] exceeds capacity, the first spillway will release water into the North Branch River. This has never happened since the dam was built so there is no precedent for potential damage. There would be a large amount of water coming into Montpelier which would drastically add to the existing flood damage.”

State officials scrambled to get personnel to monitor the structures, and despite several false alarms and high anxiety in downstream communities, the dams held fast.

“At the end of the day, we’re actually pretty fortunate with how everything performed,” Ben Green, an engineer and section chief for the DEC’s dam safety program, said in a recent interview with VTDigger. “But we had probably more close calls than we should have had.”

In the aftermath of the floods, those close calls came into focus.

In the two weeks following the flooding, state inspectors — as well as dam safety personnel called in from New York and Massachusetts — assessed nearly 400 such structures across the state, Green told lawmakers in presentations last winter.

Inspectors found that five dams — in Woodbury, Wallingford, Peru, Cabot and Washington — were effectively destroyed. Another 50 dams sustained “notable damage,” according to DEC data. In all, Vermont estimated that 57 dams were overtopped by floodwaters.

At the Wrightsville and East Barre dams, officials recorded record-high water levels, with floodwaters rising to within 10 in. of the Wrightsville Dam’s auxiliary spillway. The Waterbury Dam, meanwhile, recorded its fourth-highest water level on record.

Those findings provided state officials with something of a wake-up call, VTDigger noted.

After hearing testimony about the impact of the flood on Vermont’s dams, Sen. Chris Bray, D-Addison, and chair of the Senate Committee on Natural Resources and Energy, thought, “How do we not have this happen again?” he said.

“We are understaffed, and then the weather is more and more violent, making us more and more susceptible” to flooding, Bray told the online news site. “So how do we build a long-term pathway out of here?”

More Funding, Oversight Needed

In Vermont’s 2024 legislative session, that pathway largely took the form of Act 121, a sweeping law regulating development near waterways, improving wetlands conservation and strengthening dam safety.

State lawmakers added four positions to the dam safety program and made two others permanent, bringing the total number of state dam safety staff from five to nine — a much-needed boost for the program, officials said.

The legislation also will correct what critics say is an inconsistency in Vermont’s dam oversight system. Currently, the state DEC has jurisdiction over approximately 1,000 dams, while another 21 hydropower dams fall under the purview of the state Public Utility Commission (PUC).

Dozens of others are regulated by federal agencies, including the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and the National Park Service, among others.

Act 121 will bring the PUC’s dams under the jurisdiction of Vermont’s DEC by 2028, unless they qualify for federal oversight. The change will also standardize two different processes — a disparity that has sometimes caused anxiety for folks living close to the state’s dams.

The Vermont Legislature also added $4 million to the Dam Safety Revolving Loan Fund to fund the removal of dams that could pose a threat to communities downstream.

Previously, Vermont’s dam safety loan fund was much smaller, and could only be tapped in case of emergencies. Act 121, however, allows dam owners to access money for dam removal or renovation even before it is urgently needed.

Those monies, state officials said, will allow those landowners who might not otherwise have the resources to remove dams to access forgivable state loans to get rid of potentially hazardous structures.

Karina Dailey, a restoration ecologist at the Vermont Natural Resources Council and operator of the nonprofit’s dam removal program, said that in the aftermath of last July’s record rainfall and resulting floods, multiple landowners reached out seeking to get dams off their properties.

Deconstructing dams is not only safer for downstream communities, she explained, it is also a boon for the health of stream ecosystems.

“Certainly, a removed dam is the best dam, in our opinion,” she said in speaking to VTDigger.

Paradigm Shift

Outside of the state Legislature, officials are using other strategies to improve the condition of Vermont’s dams.

For example, the Waterbury Dam is already undergoing a multi-year renovation as part of a collaboration with the USACE to upgrade deteriorating concrete and flood gates. That project, which is currently estimated to cost roughly $80 million, is scheduled for completion in 2029.

The Vermont DEC also is in communication with the USACE about making potential improvements to the Wrightsville and East Barre dams. Renovations are being considered that would allow the dams to release water more quickly in order to build capacity ahead of expected rainfall.

That process is still in its preliminary stages, and it is not clear if or when such improvements would take place, VTDigger reported.

And even before last summer’s flooding, Vermont officials were drafting new rules governing dams. New regulations will strengthen the state’s oversight of those water barriers owned by other entities, giving state officials the authority to compel dam owners to inspect and remediate the structures.

“They are a big deal,” explained the DEC’s Kamman.

Once they go fully into effect, he said, “the state will be in a position of saying, ‘Okay owner, your dam was found to be in poor condition. It poses a risk to downstream residents. It’s not imminent, but it is a significant risk, and you need to do X, Y and Z in order to make this safe.’ That’s enforceable.”

Green, the agency’s dam safety engineer, told lawmakers in the past legislative session that the new rules amounted to a “paradigm shift in terms of how dams are regulated in the state.”

After delays caused both by COVID-19 and last year’s flooding, the regulations are slated to take effect in the summer of 2025.

Vermont officials and lawmakers say the reforms are the result of a need to keep making revisions. Climate change is exacerbating flooding in the Green Mountain State, forcing policymakers to continually adapt to heavier rainfall and more frequent deluges, events that will put further pressure on the state’s dams.

“We’re just living in a different climate,” said Bray, the chair of the Vermont Senate’s Natural Resources and Energy committee. “And we had not adapted our laws and planning practices to keep up with the hazards that we’re facing.”

Read the full article here